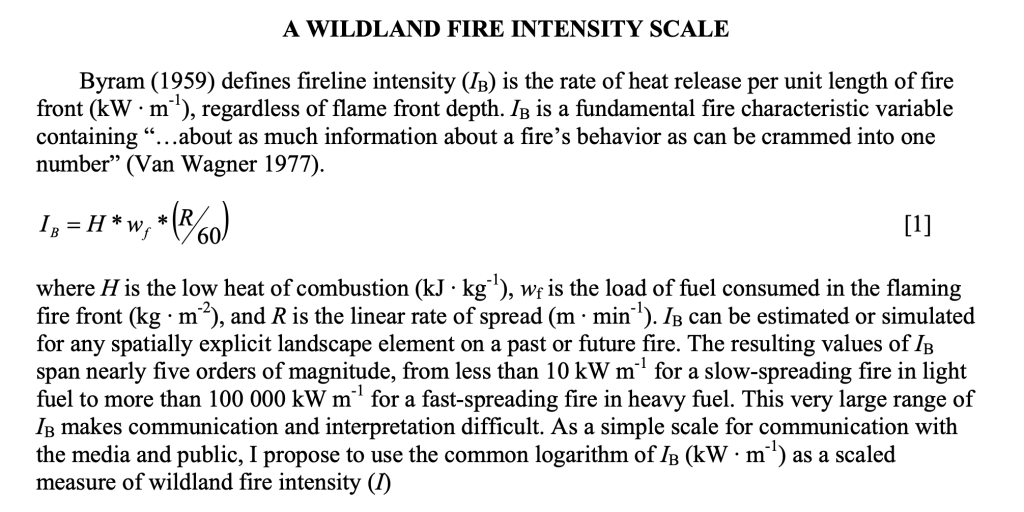

Years ago, during the 2016 Fort McMurry wildfire, I read an article that I should have bookmarked that discussed wildfire in physics terms – watts per square meter. Above some threshold, you literally and actually cannot douse the flames. Today, with the LA fires raging, I went searching and found this PDF by Joe H Scott. Seems that the standard is from Byram, G. M. 1959. Combustion of forest fuels. In: Forest fire: Control and use, 2nd edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill: chapter 1, 61-89.

Here’s the key bit from the Scott paper:

So a basic wildfire is ticking along at 10kW per meter, and a rager might be 100 to 150 megawatts per linear meter.

Goddamn. No wonder you can’t extinguish them.

By way of comparison, a gallon of gasoline has around 33 kilowatt hours of energy. If I estimate right, a big fire is equivalent to a gallon of gas burned over a 15 minute interval. Not sure that helps my intuition, and I often get stoichiometry wrong anyway.